The late nineteenth century tramway era was one of experimentation as the quest for an alternative form of propulsion to horses gathered pace in Britain and elsewhere. Steam haulage was one obvious option, having already been adopted for mainline railways but it, too, had its drawbacks in the much more confined and congested environment of urban street tramways.

Another form of traction that showed some early promise was the cable tramway, in which a fleet of non-motorised tramcars is hauled along the track by means of a continuously moving cable, which is drawn at a constant speed through a duct located between the tracks. Each individual tramcar gains traction when the operator activates a ‘grip’ that attaches the car to the moving cable through a slot beneath the vehicle, which gives access to the duct containing the cable. Conversely, the tramcar is brought to a standstill when the operator causes the grip to be released and applies the brakes.

The cable itself is propelled by means of a stationery motor or ‘winding engine’ that is located in its own dedicated engine house. Many of the early cable tramways were powered by steam engines (as used in Birmingham) but other forms of propulsion could also be used. The Birmingham cable consisted of six steel strands, each comprising nineteen steel wires plaited around a hemp rope core. A series of pulleys guides the cable along the route through a conduit under the road surface.

One major advantage with cable traction is that it does not depend on adhesion being maintained between a tramcar’s wheels and the rails, as with steam or electric traction; and, as a result, cable tramways are capable of operating on much steeper gradients than rival forms of traction.

Indeed, many of the earliest and best-known cable tramways were installed in districts that were renowned for their steep gradients. They include the world’s first such cable-operated street tramway, in San Francisco, which began operating in August 1873 and, remarkably, still operates today.

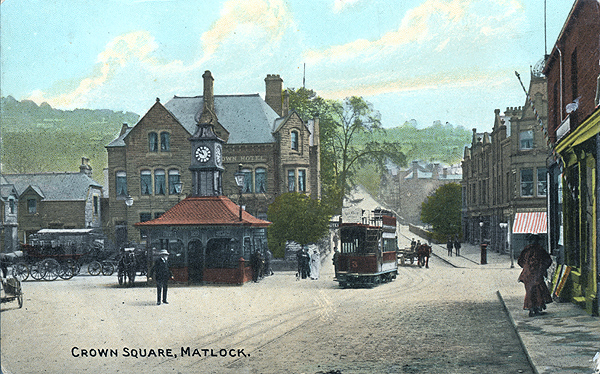

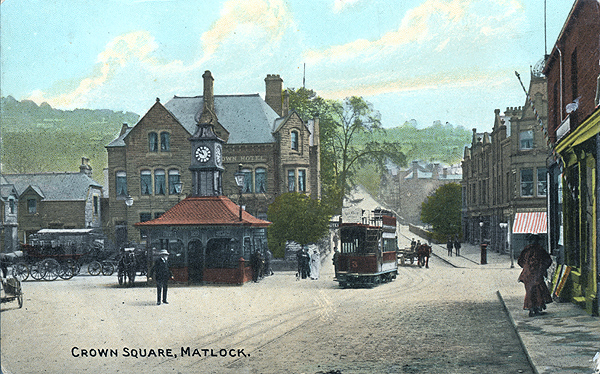

Matlock cable tram no. 3 about to depart from Crown Square, Matlock. Date unknown. Photo courtesy of Crich TMS photo archive.

Closer to home, cable-operated tramways operated in Edinburgh between 1889 and 1923 and, even closer to Crich, the incredibly steep gradients of nearby Matlock were nonetheless surmounted by the spa town’s cable tramway, which operated between 1893 and 1927.

Even today, a cable-operated street tramway – the Great Orme Tramway, which is now powered by electric motors – continues to convey tourists from Llandudno up to the summit of the Great Orme over 115 years since its inception in 1902. Technically, however, this is a funicular railway rather than a cable-operated tramway as the tramcars are permanently attached to the cable, and so start and stop when the cable does.

Great Orme Tramway cable tram no. 5 on the steep ascent up the Great Orme. Photo: Jim Dignan, 29th July 2016.

Another early cable tramway began operating in the Handsworth district of Birmingham area in March 1888. A standard gauge horse tramway operated by Birmingham Central Tramways had previously (since 1873) provided a service along the route, which ran from Colmore Row (in the city centre) to the then city boundary at Hockley Brook, with an extension serving the residential southern side of the city along Bristol Road from Suffolk Street to Bournbrook. The Hockley Brook service was not entirely satisfactory, however, partly on account of a steep gradient on Hockley Hill, which necessitated the use of additional horses to help haul the double deck tramcars, particularly when carrying a full load of passengers.

Since 1882, a number of steam operated tramways had opened up in the Birmingham area, all of which were, however, built to the narrower 3’ 6” gauge that had been prescribed by the Board of Trade for these particular services. Although steam traction offered the most obvious substitute for the original horse tramway on the Colmore Row route, it was disliked by local residents and so Birmingham Central Tramways adopted cable traction for this service instead, though the track was relaid to the by now locally regular gauge of 3’ 6”.

The initial 1½ mile route from Colmore Row to Hockley Brook opened on 24th March 1888 and a second section of the route, taking it to New Inns in Handsworth, opened on 20th April 1889. The service was operated by means of two continuous cables, each of which was hauled by one of two steam-powered winding engines located at the Whitmore Street depot in Hockley, one cable serving Hockley to Colmore Row section, the other the Hockley to New Inns section.

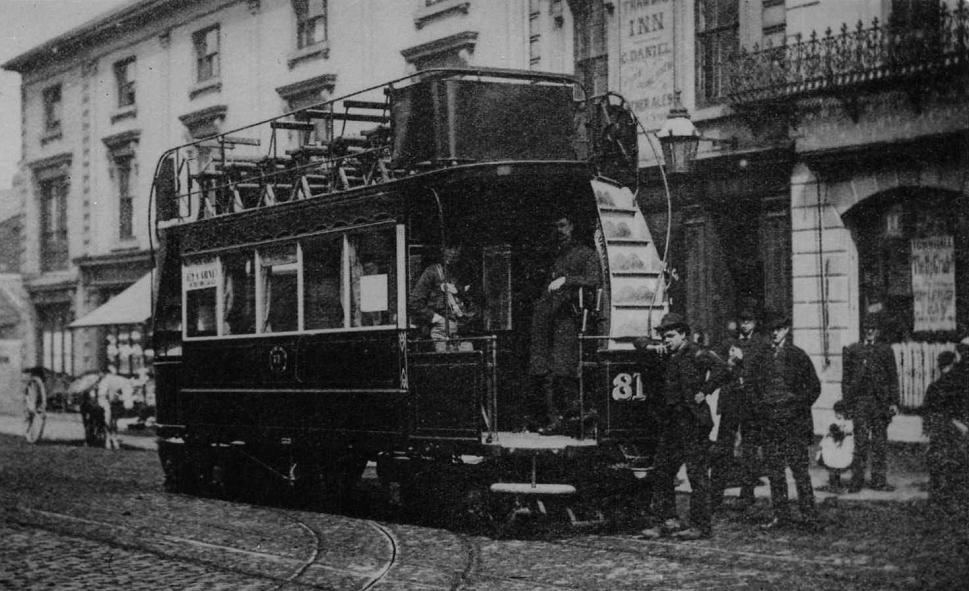

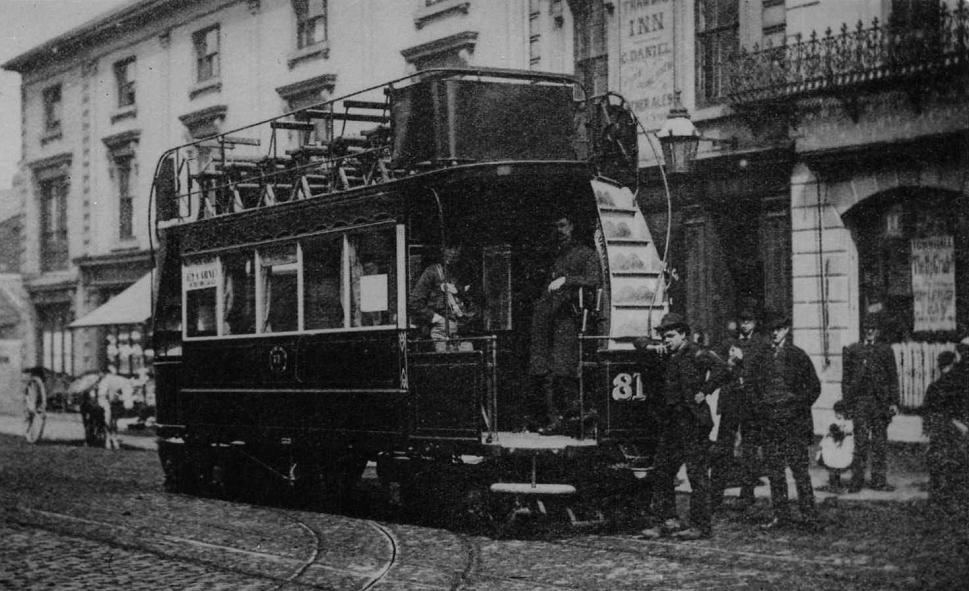

Birmingham Central Tramways cable tram no. 81 stopped at Hockley Brook in July 1990, showing cable duct between the tracks. Photo: William Jerome Harrison.

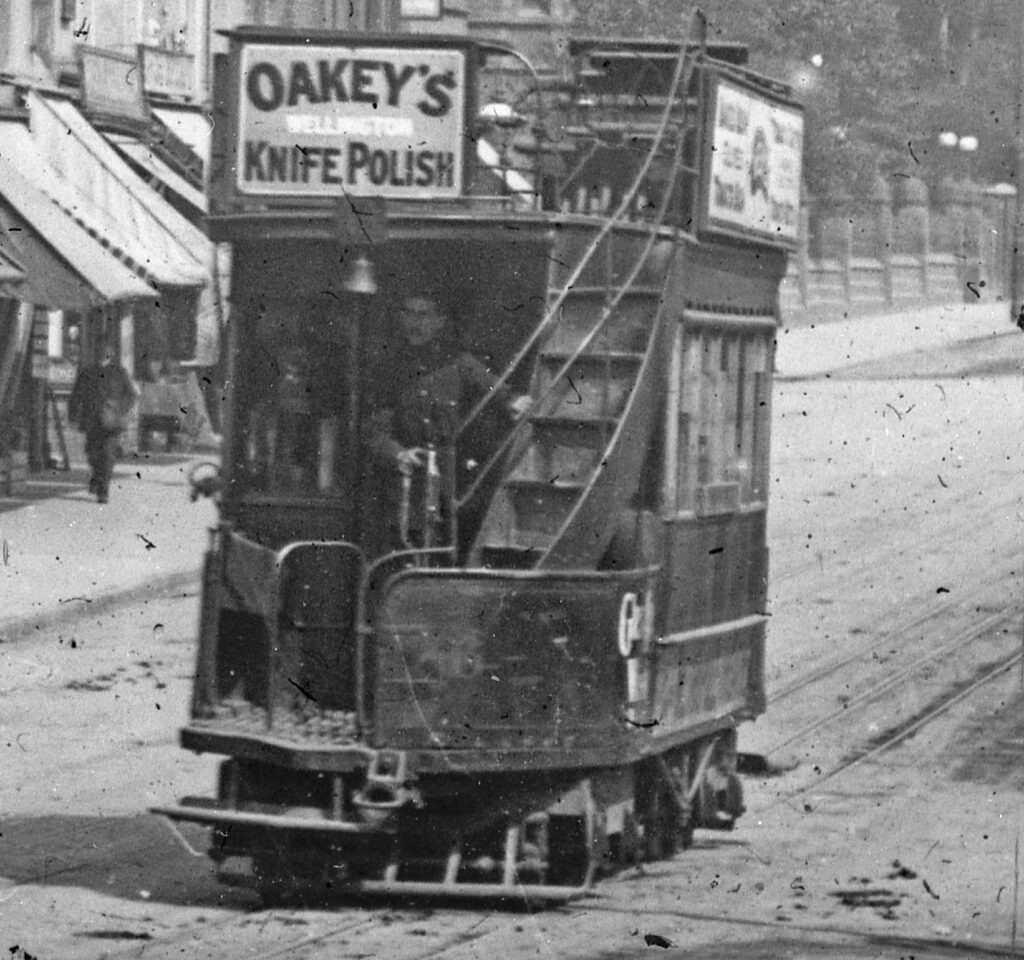

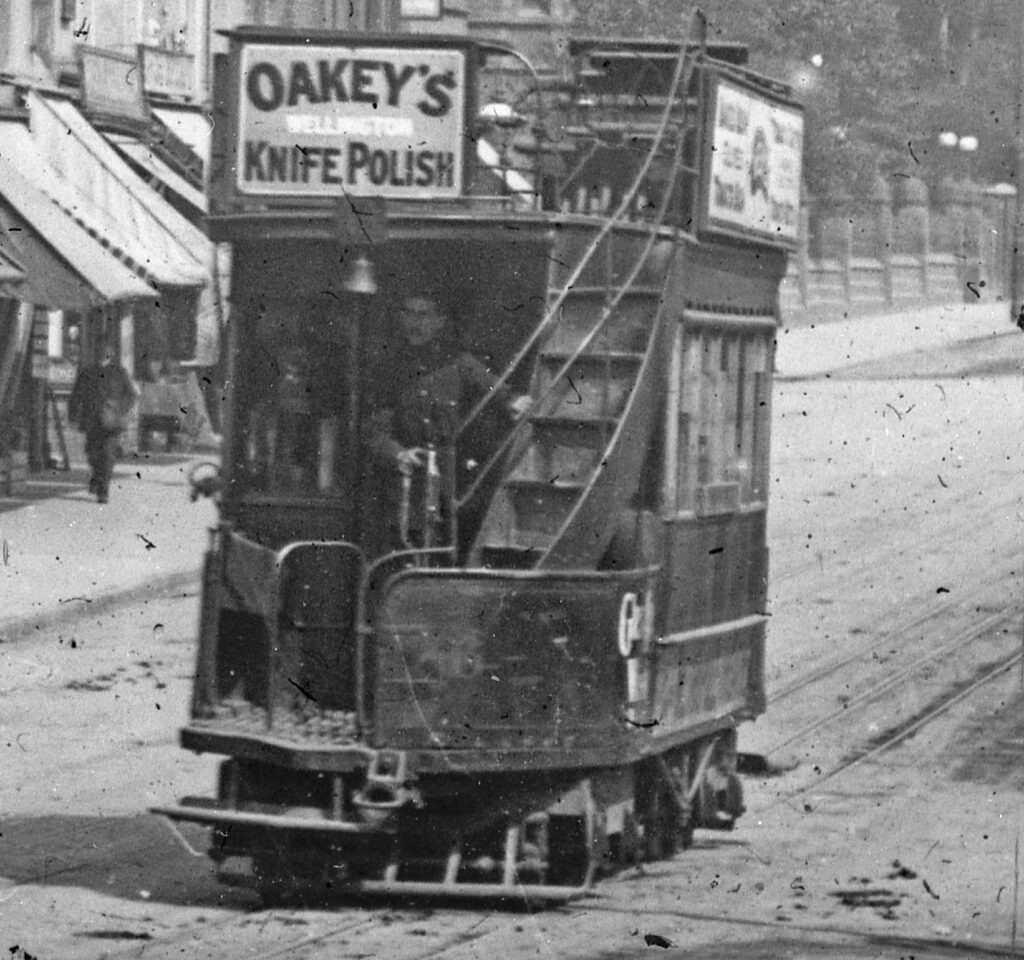

Most of the tramcars were double deck open-top vehicles with a half canopy over the drivers’ platforms and were mounted on two four-wheel bogies. In appearance, the cable trams somewhat resembled shorter versions of contemporary steam tram trailers and had similar platform arrangements with the steps being located at the corner of the platform instead of at the side.

Unidentified Birmingham Central Tramways car showing position of steps and staircase. Photo courtesy of David Beardsell.

The first batch of twenty tramcars – numbered 75 – 94 – was built in 1888 by the Falcon works in Loughborough to service the Colmore to Hockley Brook route, though this was followed by a further twenty four double deck cable trams that were delivered in two batches (from Metropolitan and Falcon works in 1889 and 1895 respectively). In addition, the company also operated a smaller number of single deck toast-rack cable trams for a while.

When it came to replacing the far less hilly Bristol Road extension of the original horse tramway, Birmingham Central Tramways had initially proposed to electrify the tramway using overhead tramlines, but met with implacable opposition from both Birmingham Council and an influential local family whose estate lay adjacent to the route.

Consequently, the Company resorted, in 1890, to yet another form of traction, using battery operated electric tramcars (known as ‘accumulator’ cars), which also operated on tracks that were relaid to 3’6” gauge. The battery-operated tramcars looked superficially similar to the cable trams apart from the fact that they were somewhat longer and had six, rather than five window bays. Neither of these two forms of propulsion proved entirely satisfactory, however, and just over a decade later, in 1901, the Bristol Road service became the first tramway in Birmingham to be powered by means of overhead wires, having finally overcome the initial resistance to the idea.

One of the problems with cable operated tramways was the wear and tear on the cables themselves, which frequently had to be replaced – an expensive business – if they were not to fray; and if they did fray they could become jammed in the grip, which could not be released, meaning that the tramcar could not be stopped until the cable itself was stopped.

The battery operated tramway experienced a different set of problems as the lead-acid batteries, or accumulators, were housed beneath the passenger seats, which was not an ideal arrangement as an accident could clearly have had lethal consequences. In addition, passengers frequently complained about acid fumes and occasional damage to clothing. The weight of the batteries was an additional problem, particularly as the charge ran down, which risked leaving the tramcar stranded without power. Even when fully charged, the maximum distance that could be covered was about 30 miles.

The forty four cable cars and all but two of the fourteen accumulator cars (which had already been withdrawn in 1894) were transferred to a new company, the City of Birmingham Tramways Company Ltd., on 29th September, 1896. However, the cable cars continued operating until 30th June, 1911, which is when the company’s lease came to an end.

Birmingham Central Tramways cable car at the Black Country Living Museum in Dudley during the 1970s, shortly after it was taken into preservation. Photo from the TLRS collection.

Most of the cable trams were broken up when operations finished; however, one cable tram body is known to have survived for a number of years as a summer house in Smethwick before being donated for preservation to the Black Country Museum, where it was used for a time as a shelter. As the body has five window bays it is clearly from one of the cable operated tramcars and is thought to have been one of the original batch that served the Colmore Row to Hockley Brook route.

After storing it for many years, the Black Country Museum very generously offered to donate this extremely significant vehicle to the tramway museum in 2015. As a representative of a fourth form of tram traction it fills an important gap in the museum’s existing collection of horse, steam and electric tramcars. The remains of the tramcar were removed to the museum’s off-site storage facility at the end of November 2017.

The tramway museum also has a yoke, which was located in the concrete cable chamber, the function of which was to act as a transverse sleeper to hold the outside rails and slot rails in position.

Yoke from Birmingham Central Tramways, which was designed to hold the outside and slot rails in position. Photo: Andy Bailey

In addition to what remains of the tramcar itself, a working model of the car’s underframe and grip gear mechanism which was commissioned by the tramway company, is also in preservation at the National Tramway Museum in York.

Another cable tram to have survived into preservation is Edinburgh & District Tramways no. 226, which was subsequently converted into an electric tramcar in 1923 before being withdrawn from service in 1938 and converted into a holiday home. It is currently being restored to its original guise as a cable car in its home city.